I was brought up to cheat

So long as the referee

Wasn’t looking

If a tree falls in a forest and no one is around to hear it, does it really make a sound?

If a basketball player violates a rule and the referee doesn’t see it, was there really a violation?

The answer to both questions is the same – correct?

* * * * *

I’ve been refereeing basketball since 2001.

Now that I’m retired, I can do a lot more games during the week. I can do middle-school games (which tip off at 315p on Tuesdays, Wednesdays, and Thursdays), junior varsity games (which usually start at 530p on weekdays but may start as early as 400p at some schools), and varsity games (which most often begin at 700p or 715p on weekdays).

|

Plus I can continue to referee county recreation department and CYO games, which begin at 900a on Saturdays and at noon on Sundays, and continue until well after dark.

Refereeing is the way I get in my exercise in the winter – when the temperatures are in the thirties and forties, I lose all interest in biking or hiking.

Recently, I’ve been doing games almost every day. I’m currently in the middle of a ten-day stretch where I have at least one game – sometimes two – every day.

* * * * *

As of now, it looks like I’ll referee 41 games in January. (That number should have been higher, but five of my games have been postponed due to bad weather.)

That breaks down to 17 recreation department and CYO games, nine public middle-school games, a freshmen boys’ game at a private high school, eight high-school JV games (mostly at public schools), and six high-school varsity games (at both public and private schools).

Most of those games involved boys and but a fair number were girls’ games.

Two of my rec department games involved 6th-grade boys. The level of play in those games was nothing to write home about.

|

My most challenging game was a boys’ varsity game featuring some very fast and physical players. My refereeing partner in that game was a Division I college referee, which was comforting.

* * * * *

I had to take a ten-session training class and pass a 100-question multiple-choice rules exam to become a referee – and I have to pass a written refresher exam every fall to maintain my status.

Maybe you played high-school basketball, or watch a lot of basketball on TV. But I guarantee you that you wouldn’t answer more than a quarter of the questions on the rules exam correctly unless you studied the rulebook closely before you took that test.

But the hardest part of being a referee isn’t memorizing the rules. The bigger challenge is learning when to blow my whistle and call a foul or a violation, and when not to blow the whistle – which is a decision that depends on the age and skill level of the players and a number of other factors.

* * * * *

You’ve heard the saying, “No harm, no foul.” It’s not that simple, but there is quite a bit of truth in that statement.

For example, last weekend I had a 6th-grade boys’ rec department game that featured one player who was not only bigger and stronger than his opponents, but also a more skilled player. Several times, he successfully dribbled through the defense and made a layup. Each time he did that, there was contact.

The contact didn’t slow this kid down, or knock him off course, or interfere with his shots. In other words, it was what the rule book terms “incidental contact” – which is defined as contact which does not hinder a player from completing normal offensive or defensive movements. Incidental contact is not a foul.

|

If you called a foul every time there was contact between two 6th-grade players, you’d be calling fouls on almost every possession – the kids wouldn’t be able to play because the referees would be constantly interrupting the action.

In a high-school game, I would have been more likely to call a foul because players at that level are more skilled, and you hold them to a higher standard. Also, even relatively minor contact may still affect the outcome of a play at that level.

* * * * *

The “No harm, no foul” principle doesn’t apply only to fouls, of course.

If you’ve ever played basketball, or have a son or daughter who has played basketball, you know about the “three seconds” rule. In a nutshell, that rule holds that an offensive player can’t stand in the free-throw lane for more than three seconds.

If you go to any low-level kids’ basketball game, you’ll hear coaches and parents yelling “Three seconds!” every time an opponent whose team has the ball is seen standing within the boundaries of the free-throw lane.

Are they doing that because the opponent is getting an advantage? Most of the time, the answer to that question is “Absolutely not!” The kid who is standing in the lane isn’t the 6th-grade equivalent of Wilt Chamberlain – someone who is bigger than the defenders, and who is pretty much unstoppable when he positions himself or herself in the lane close to the basket until a teammate lobs a high pass to him – a pass that none of the smaller defenders can reach – which he or she catches and deposits into the basket.

Usually, the kids that everyone yells “Three seconds!” about aren’t the better players. They aren’t particularly big, and they’re no real threat to get the ball while positioned in the lane and then score. They are in the lane simply because they’ve forgotten that they’re not supposed to stand in the lane.

|

If you call such a player for a three seconds violation, all you’ve done is embarrass him or her. The violation had no effect on the game – the violator’s team got no advantage whatsoever. Calling a three seconds violation in that situation has about as much effect on the game as a player’s mismatched socks or bad haircut.

By the way, the first thing that the referee who taught my training class said was, “Calling three seconds is the sign of a weak referee!” He knew that the parents who yell “Three seconds!” aren’t worried about the opponents getting an advantage – they are simply trying to goad the referee into doing something that helps their child’s team.

And he knew that a referee who focuses his or her attention on three seconds violations is probably missing other violations or fouls that have a much greater impact on the outcome of the game.

Of course, if a kid camps out in the lane long enough, you do have to call a three seconds violation eventually. You hope that calling it one time is sufficient to make the point.

* * * * *

It’s bad enough that parents and coaches in low-level games are so consumed with winning that they will verbally goose the refs in hopes of getting an edge.

What’s even more annoying is that most of those parents and coaches don’t even know what the three seconds rule says.

Here’s an excerpt from rule 9.7.1 of the National Federation of High Schools basketball rulebook:

A player shall not remain for three seconds in . . . his/her free-throw lane . . . while the ball is in control of his/her team in his/her frontcourt.

The key phrase here is “while the ball is in control of his/her team.” A team is in control of the ball when one of its players is holding or dribbling or passing the ball. A team is NOT in control after a player takes a shot, or during the battle for rebounds.

|

Let’s say one of my teammates launches a shot and I run into the free-throw lane in hopes of grabbing the rebound if the shot is errant. When it does miss, I grab the rebound and immediately shoot the ball at the basket. My shot misses, but a teammate grabs that rebound and tries to put the ball in the basket. He misses, but I grab the next rebound and take yet another shot – finally, the ball goes in.

I may have been in the lane for ten seconds, but that was legal because my team was never in control of the ball for as long as three seconds. (There’s no team control while a shot is in flight, or the ball is bouncing on the rim.) But you’ll hear cries of “Three seconds!” every time that happens.

When you’re a natural-born passive-aggressive type, it’s tempting to walk over to the coach or parent, give him or her a big smile, and explain the niceties of the three seconds rule in a tone of voice that is ever so polite, but also loud enough to be heard in the back row of the bleachers.

But I would never do such a thing, of course. I simply turn the other cheek and go back to refereeing.

* * * * *

(NOTE: Most of the high schools in this area don't have dressing rooms reserved for officials – referees dress in classrooms or offices. The photos above were taken in the girls PE office where I and my partner put on our uniforms before a recent high school game.)

* * * * *

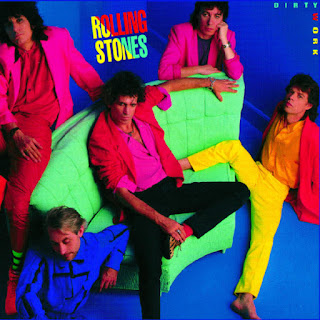

“Winning Ugly” was released in 1986 on Dirty Work – which was the Rolling Stones’ 20th American studio album.

|

Mick Jagger and Keith Richards were not getting along when this album was recorded. Jagger had just released his first solo album, and Richards thought he wasn’t giving enough time and attention to the Stones.

The backup singers on Dirty Work included legendary musicians Jimmy Cliff, Don Covay, Bobby Womack, Tom Waits, and Patty Scialfa (a/k/a Mrs. Bruce Springsteen), plus actress Beverly D’Angelo (a/k/a Mrs. Clark Griswold).

|

| Beverley D’Angelo and Chevy Chase in National Lampoon’s Vacation |

Click here to listen to “Winning Ugly.”

Click on the link below to buy the song from Amazon: