You can take it or leave it

This is me

This is who I am!

One of the many books I requested from my public library based on the late Larry McMurtry’s recommendation was Wallace Stegner’s memoir, Wolf Willow, which McMurtry called “a wonderful book.” (He was right.)

|

Stegner was born in 1909. He spent much of his childhood in a tiny and isolated farming town in Saskatchewan called Eastend.

McMurtry grew up several decades later in Archer City, an equally obscure plains town in the Texas Panhandle that is 1500 miles from Eastend as the crow flies but probably wasn’t all that different culturally. I’m sure Wolf Willow spoke to him in a very personal sense.

From Wolf Willow:

I may not know who I am, but I know where I am from. I can say to myself that a good part of my private and social character, the kinds of scenery and weather and people and humor I respond to, the prejudices I wear like dishonorable scars . . . the virtues I respect and the weaknesses I condemn, the code I try to live by, the special ways I fail at it and the kind of shame I feel when I do . . . have been in good part scored into me by that little womb-village and the lovely lonely exposed prairie of the homestead.

I grew up in a very different environment – the small city in Missouri where I spent my childhood in the fifties and sixties was very far removed from the isolated frontier village where Stegner lived a hundred years ago – but like Stegner, I know where I am from.

* * * * *

More from Wolf Willow:

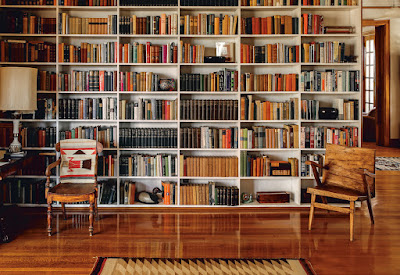

Once I was comparing my background with that of an English novelist friend. Where he had been brought up in London, taken from the age of four to the Tate and the National Gallery, sent traveling on the Continent for every school holiday, taught French and German and Italian, given access to bookstores, libraries, and British Museums, made familiar from infancy with the conversation of the eloquent and the great, I had grown up in this dung-heeled sagebrush town on the disappearing edge of nowhere, utterly without painting, without sculpture, with architecture, almost without music and theatre, without conversation or languages or travel or stimulating instruction, without libraries or museums bookstores, almost without books.

My hometown wasn’t a “dung-heeled sagebrush town on the disappearing edge of nowhere.” Unlike Eastend, it had a good public library that I took full advantage of, and there were a number of music teachers who taught piano and violin and other instruments – almost all of my childhood friends learned to play a musical instrument. We also had movies and radio and television, which exposed us to the wider world.

|

| Wallace Stegner |

But while Joplin wasn’t as far culturally from New York City and Chicago as the prairie town where Stegner grew up, we still had a cultural inferiority complex. Joplin had an airport serviced by commercial airlines and was situated on a major interstate highway, but I never flew anywhere until I was almost 18, and my family rarely used that highway to travel anywhere more than an hour or two away.

I read constantly. But reading about England or France or Italy isn’t the same thing as being there. And reading a Shakespeare or George Bernard Shaw play isn’t the same as seeing that play performed.

There are still dozens – perhaps hundreds – of place names and other proper nouns that I can spell and define, but am reluctant to speak in public out of fear that I will mispronounce them, which would reveal to my more sophisticated friends and associates that I’m a redneck hick. (You don’t learn how to pronounce French aphorisms or the names of Tolstoy characters by reading books.)

* * * * *

Despite his very humble beginnings, Wallace Stegner eventually got a Ph.D., and taught at Harvard and Stanford. He wrote a dozen-odd novels, a dozen-odd nonfiction books, and several collections of essays and short stories, and was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, a National Book Award, and many other honors.

I’m guessing he was always of two minds about people like that English novelist friend. On the one hand, he was probably somewhat intimidated by their sophistication and politesse. But on the other hand, I’m sure he was fiercely proud and would have been happy to invite anyone who condescended to him to step outside.

* * * * *

“Boondocks” was a 2005 hit for the very successful country music group, Little Big Town.

|

| Little Big Town |

It’s a great song, but I wish an edgier artist than Little Big Town had recorded it. Nothing against them, but I think the song would from benefit if it was performed by someone who sounded like he had a big chip on his shoulder – someone who would happily take a swing at you if you gave him an excuse. That would take the record to a whole ’nother level.

Click here to see the official music video for “Boondocks.”

Click on the link below to buy the song from Amazon: